Журнал «Травма» Том 18, №3, 2017

Вернуться к номеру

Хворобомодифікуюча терапія остеоартриту в чинних рекомендаціях: уроки минулого та можливості для майбутнього

Авторы: Головач І.Ю.

Клінічна лікарня «Феофанія» Державного управління справами, м. Київ, Україна

Рубрики: Травматология и ортопедия

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

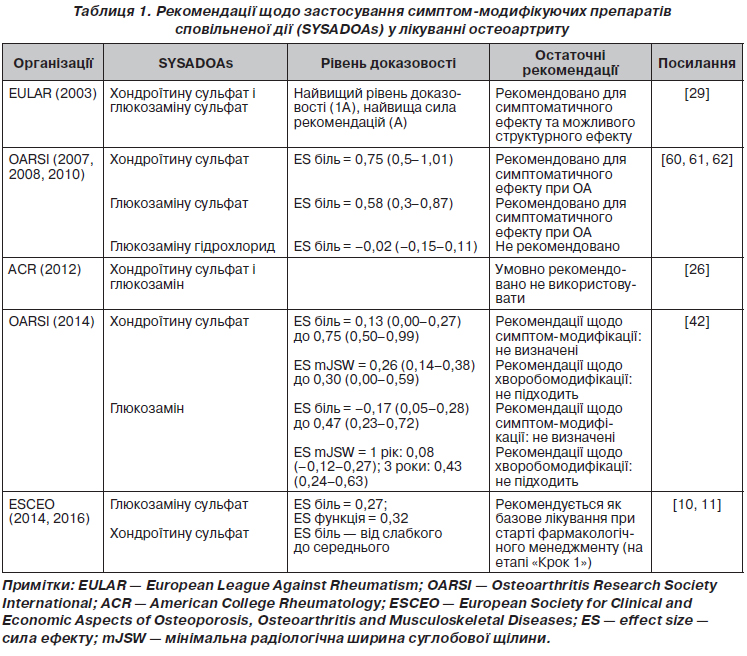

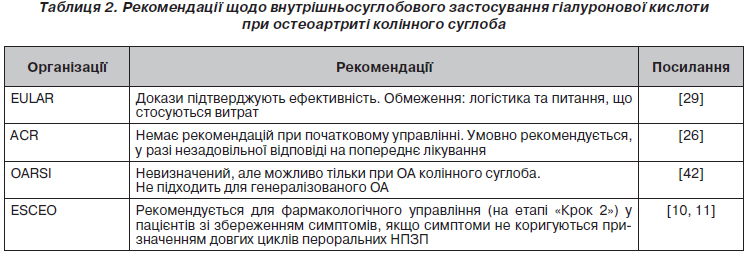

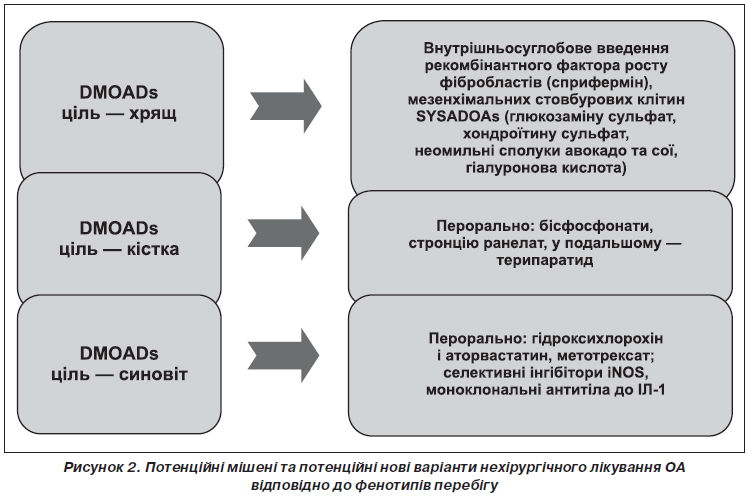

У статті позначені сучасні погляди на лікування остеоартриту з позицій структурно-модифікуючої терапії. Подані останні рекомендації з нехірургічного лікування остеоартриту, вказано на їх неоднорідність і проаналізовано причини суперечливої позиції, особливо у питаннях використання симптом-модифікуючих препаратів сповільненої дії (глюкозаміну сульфату, хондроїтину сульфату та гіалуронової кислоти). Гармонізація й узгодження останніх рекомендацій EULAR, OARSI, ACR, ESCEO та створення єдиного покрокового алгоритму дозволить поліпшити наслідки та ефективність лікування остеоартриту, стане ключем до поліпшення управління цим захворюванням. В оновленому в 2016 році алгоритмі ESCEO з лікування остеоартриту колінних суглобів викладена узгоджена думка експертів, що використання симптом-модифікуючих препаратів сповільненої дії (SYSADOAs) слід вважати безпечнішим і більш комплексним підходом до лікування остеоартриту, ніж безперервний прийом парацетамолу як перший крок менеджменту остеоартриту колінного суглоба. Сучасні зміни парадигми в лікуванні остеоартриту полягають насамперед у визнанні остеоартриту як складного гетерогенного захворювання з декількома фенотипами, кожен з яких вимагатиме різних підходів до оптимізації лікування. Так, згідно з останніми дослідженнями, виділяють запальний, травматичний, кістка-опосередкований та хрящ-опосередкований фенотипи остеоартриту. Головною метою спроб виділити фенотипові варіанти перебігу остеоартриту є перш за все індивідуалізація лікування, оскільки різні патогенетично-клінічні фенотипи хвороби вимагають різних терапевтичних стратегій. Потенційно кожний фенотип може лікуватися засобами таргетного (цілеспрямованого) впливу, що потребує ранньої стратифікації пацієнтів за фенотипами та відповідної стратифікації лікарських засобів для лікування остеоартриту. Список невдач, уроки минулих досліджень, обмежений успіх клінічного розвитку нових агентів для дієвого лікування остеоартриту може бути частково згладжений оптимістичними дослідними гіпотезами, однак результат їх застосування залежатиме від правильного відбору пацієнтів для випробувань та цілеспрямованого використання у пацієнтів із відповідними фенотипами хвороби.

В статье обозначены современные взгляды на лечение остеоартрита с позиций структурно-модифицирующей терапии. Представлены последние рекомендации по нехирургическому лечению остеоартрита, указано на их неоднородность и проанализированы причины противоречивой позиции, особенно в вопросах использования симптом-модифицирующих препаратов замедленного действия (глюкозамина сульфата, хондроитина сульфата и гиалуроновой кислоты). Гармонизация и согласования последних рекомендаций EULAR, OARSI, ACR, ESCEO и создание единого пошагового алгоритма позволят улучшить последствия и эффективность лечения остеоартрита, что станет ключом к улучшению управления этим заболеванием. В обновленном в 2016 году алгоритме ESCEO по лечению остеоартрита коленных суставов изложено согласованное мнение экспертов, что использование симптом-модифицирующих препаратов замедленного действия (SYSADOAs) следует считать безопасным и более комплексным подходом к лечению остеоартрита, чем непрерывный прием парацетамола как первый шаг менеджмента остеоартрита коленного сустава. Современные изменения парадигмы в лечении остеоартрита заключаются прежде всего в признании остеоартрита как сложного гетерогенного заболевания с несколькими фенотипами, каждый из которых требует различных подходов к оптимизации лечения. Так, согласно последним исследованиям, выделяют воспалительный, травматический, кость-опосредованный и хрящ-опосредованный фенотипы остеоартрита. Главной целью попыток выделить фенотипические варианты течения заболевания является прежде всего индивидуализация лечения, поскольку патогенетически различные клинические фенотипы болезни требуют различных терапевтических стратегий. Потенциально каждый фенотип может лечиться средствами таргетного (целенаправленного) действия, что требует ранней стратификации пациентов с фенотипами и соответствующей стратификации лекарственных средств для лечения остеоартрита. Список неудач, уроки прошлых исследований, ограниченный успех клинического развития новых агентов для эффективного лечения остеоартрита может быть частично сглажен оптимистическими исследовательскими гипотезами, однако результат их применения будет зависеть от правильного отбора пациентов для испытаний и целенаправленного использования у больных с соответствующими фенотипами болезни.

The modern views on the treatment of osteoarthritis from the perspective of structural-modifying therapy are defined in the article. The latest recommendations on the non-surgical treatment of osteoarthritis are presented; their heterogeneity is indicated, and the causes of the conflicting position, especially in the use of symptom-modifying slow-acting drugs (SYSADOAs) (glucosamine sulfate, chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid), are analyzed. Harmonization and coordination of the latest

EULAR, OARSI, ACR, ESCEO recommendations and creation of a single step-by-step algorithm will improve the effects and effectiveness of the osteoarthritis treatment and will be the key to the improvement of the disease management. The ESCEO algorithm for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee joints, updated in 2016, outlines the shared opinion of experts according to which the use of SYSADOAs should be considered a safer and more comprehensive approach to the treatment of osteoarthritis than the continuous use of paracetamol as the first step in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Modern paradigm changes in the treatment of osteoarthritis mostly involve the recognition of osteoarthritis as a complex heterogeneous disease with several phenotypes, each of which requires different approaches to the optimization of treatment. So, according to the latest studies, the inflammatory, traumatic, bone-mediated and cartilage-mediated phenotypes of osteoarthritis are distinguished. The main goal of attempts to distinguish phenotypic variants of the course of the disease is, first of all, the individualization of treatment, because pathogenetically different clinical phenotypes of the disease require different therapeutic strategies. Potentially, each phenotype needs and can be treated with target (well-targeted) action, which requires early stratification of patients by phenotypes and appropriate stratification of drugs for osteoarthritis. The list of failures, the lessons of past researches, the limited success of the clinical development of new agents for the effective treatment of osteoarthritis can be partially mitigated by optimistic research hypotheses, but the result of their application will depend on the correct selection of patients for testing and well-targeted use in patients with the corresponding phenotypes of the disease.

остеоартрит; лікування; хворобомодифікуюча терапія; симптом-модифікуючі препарати сповільненої дії; фенотипи остеоартриту; глюкозаміну сульфат; хондроїтину сульфат; рекомендації

остеоартрит; лечение; болезнь-модифицирующая терапия; симптом-модифицирующие препараты замедленного действия; фенотип остеоартрита; глюкозамина сульфат; хондроитина сульфат; рекомендации

osteoarthritis; treatment; disease-modifying therapy; symptom-modifying slow-acting drugs; phenotype of osteoarthritis; glucosamine sulfate; chondroitin sulfate; recommendations

1. Головач И.Ю. Остеоартрит: современные фундаментальные и прикладные аспекты патогенеза заболевания. Боль. Суставы. Позвоночник. 2014; 3(15): 54-58.

2. Alexandersen P., Karsdal M.A., Qvist P., Reginster J.Y., Christiansen C. Strontium ranelate reduces the urinary level of cartilage degradation biomarker CTX-II in postmenopausal women. Bone, 2007; 40(1): 218-222. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.028.

3. Altman R.D. Glucosamine therapy for knee osteoarthritis: pharmacokinetic considerations. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol., 2009; 2: 359-371. doi: 10.1586/ecp.09.17.

4. Bannuru R.R., Natov N.S., Dasi U.R., Schmid C.H., McAlindon T.E. Therapeutic trajectory following intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection in knee osteoarthritis — meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2011; 19: 611-619. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.014.

5. Bannuru R.R., Natov N.S., Obadan I.E., Price L.L., Schmid C.H., McAlindon T.E. Therapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum., 2009; 61: 1704-1711. doi: 10.1002/art.24925.

6. Bannuru R.R., Vaysbrot E.E., Sullivan M.C., McAlin-don T.E. Relative efficacy of hyaluronic acid in comparison with NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum., 2014; 43: 593-599. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.10.002.

7. Bijlsma J.W., Berenbaum F., Lafeber F.P. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet, 2011; 377: 2115-2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60243-2.

8. Bjordal J.M., Klovning A., Ljunggren A.E., Slordal L. Short-term efficacy of pharmacotherapeutic interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain: A metaanalysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Eur J Pain, 2007; 11: 125-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.013.

9. Brandt K.D., Mazzuca S.A., Katz B.P., et al. Effects of doxycycline on progression of osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52(7): 2015-25. doi: 10.1002/art.21122.

10. Bruyere O., Cooper C., Pelletier J.P. et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: A report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014; 44: 253-263. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014.

11. Bruyère O., Cooper C., Pelletier J-P., et al. A consensus statement on the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) algorithm for the management of knee osteoarthritis — From evidence-based medicine to the real-life setting. Semin Arthritis Rheum., 2016; 45(4): S3-S11. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.11.010.

12. Cambell K.A., Erickson B.J., Saltzman B.M. et al. Is Local Viscosupplementation Injection Clinically Superior to Other Therapies in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Systematic Review of Overlapping Meta-analyses. Arthroscopy, 2015; 31(10): 2036-2045. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.03.030.

13. Chevalier X., Eymard F., Richette P. Biologic agents in osteoarthritis: hopes and disappointments. Nat Rev Rheumatol., 2013; 9: 400-410. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.44.

14. Clegg D.O., Reda D.J., Harris C.L., et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N. Engl. J. Med., 2006; 354: 795-808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052771.

15. Cohen S.B., Proudman S., Kivitz A.J., et al. A randomized, double-blind study of AMG 108 (a fully human monoclonal antibody to IL-1R1) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther., 2011; 3(4): R125. doi: 10.1186/ar3430.

16. Conaghan P.G. Osteoarthritis in 2012: parallel evolution of OA phenotypes and therapies. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013; 9(2): 68-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.225.

17. Cutolo M., Berenbaum F., Hochberg M. et al. Commentary on recent therapeutic guidelines for osteoarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum., 2015; 44(6): 611-617. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.12.003.

18. da Costa B.R., Nuesch E., Reichenbach S., Juni P., Rutjes A.W. Doxycycline for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev., 2012; 11: CD007323. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007323.pub3.

19. de Lange-Brokaar B.J., Ioan-Facsinay A., van Osch G.J. et al. Synovial inflammation, immune cells and their cytokines in osteoarthritis: a review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012; 20:1484-1499. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.027.

20. Dinarello C.A., Simon A., van der Meer J.W. Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in a broad spectrum of diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 2012; 11: 633-652. doi: 10.1038/nrd3800.

21. Elder B.D., Athanasiou K.A. Systematic assessment of growth factor treatment on biochemical and biomechanical properties of engineered articular cartilage constructs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2009; 17(1): 114-23. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.006.

22. Felson D.T., Neogi T. Osteoarthritis: is it a disease of cartilage or of bone? Arthritis Rheum, 2004; 50(2): 341-344. doi: 10.1002/art.20051.

23. Goldring M.B., Berenbaum F. Emerging Targets in Osteoarthritis Therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015; 22: 51-63. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2015.03.004.

24. Hellio le Graverand M.P., Clemmer R.S., Redifer P. et al. A 2-year randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study of oral selective iNOS inhibitor, cindunistat (SD-6010), in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis, 2013; 72(2): 187-95. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202239.

25. Henrotin Y., Marty M., Mobasheri A. What is the current status of chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis? Maturitas, 2014; 78: 184-187. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.04.015.

26. Hochberg M.C., Altman R.D., April K.T. et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken), 2012; 64: 465-474.

27. Hochberg M.C., Zhan M., Langenberg P. The rate of decline of joint space width in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of chondroitin sulfate. Curr. Med. Res. Opin., 2008; 24: 3029-3035. doi: 10.1185/03007990802434932 .

28. Hunter D.J., Pike M.C., Jonas B.L., Kissin E., Krop J., McAlindon T. Phase 1 safety and tolerability study of BMP-7 in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord., 2010; 11: 232-236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-232.

29. Jordan K.M., Arden N.K., Doherty M., et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis, 2003; 62: 1145-1155.

30. Kahan A., Uebelhart D., De Vathaire F., Delmas P.D., Reginster J.Y. Long-term effects of chondroitins 4 and 6 sulfate on knee osteoarthritis: the study on osteoarthritis progression prevention, a two-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum., 2009; 60: 524-533. doi: 10.1002/art.24255.

31. Karsdal M.A., Michaelis M., Ladel C. et al. Disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis (DMOADs) of the knee and hip: lessons learned from failures and opportunities for the future. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2016; 24: 2013-2021. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.07.017.

32. Kotevoglu N., Iyibozkurt P.C., Hiz O., Toktas H., Kuran B. A prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing the efficacy of different molecular weight hyaluronan solutions in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Int., 2006; 26: 325-330. DOI: 10.1007/s00296-005-0611-0.

33. Kraus V. et al. Call for Standardized Definitions of Osteoarthritis and Risk Stratification for Clinical Trials and Clinical Use. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015; 23(8): 1238-1241. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.036.

34. Larkin J., Lohr T.A., Elefante L. et al. Translational development of an ADAMTS-5 antibody for osteoarthritis disease modification. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2015; 23(8): 1254-66. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.778.

35. Lee K., Lanske B., Karaplis A.C. et al. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide delays terminal differentiation of chondrocytes during endochondral bone development. Endocrinology 1996; 137(11): 5109-5118. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895385.

36. Lee Y.H., Woo J.H., Choi S.J., Ji J.D., Song G.G. Effect of glucosamine or chondroitin sulfate on the osteoarthritis progression: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int., 2010; 30: 357-363. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-0969-5.

37. Leff R.L., Elias I., Ionescu M., Reiner A., Poole A.R. Molecular changes in human osteoarthritic cartilage after 3 weeks of oral administration of BAY 12-9566, a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3): 544-549. PMID: 12610815.

38. Lo K.W., Ulery B.D., Ashe K.M., Laurencin C.T. Studies of bone morphogenetic protein-based surgical repair. Adv Drug Deliv Rev., 2012; 64(12): 1277-91. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.03.014.

39. Lohmander L.S., Hellot S., Dreher D. et al. Intraarticular sprifermin (recombinant human fibroblast growth factor 18) in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol, 2014; 66(7): 1820-31. doi: 10.1002/art.38614.

40. Matthews G.L., Hunter D.J. Emerging drugs for osteoarthritis. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs., 2011; 16: 479-491. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2011.576670.

41. Mazzuca S.A., Brandt K.D.,Eyre D.R. et al. Urinary levels of type II collagen C-telopeptide crosslink are unrelated to joint space narrowing in patients with knee osteoarthritis / An. Rheum Dis., 2006; 65(8): 1055-1059. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041582.

42. McAlindon T.E., Bannuru R.R., Sullivan M.C. et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2014; 22: 363-388. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003.

43. Michel B.A., Stucki G., Frey D. et al. Chondroitins 4 and 6 sulfate in оsteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum., 2005; 52: 779-786. doi: 10.1002/art.20867.

44. Mobasheri A., Bay-Jensen A.-C., van Spil W.E., Larkin J., Levesque M.C. Osteoarthritis Year in Review 2016: biomarkers (biochemical markers). Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2017; 25: 199-208. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.12.016.

45. Moore E.E., Bendele A.M., Thompson D.L. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-18 stimulates chondrogenesis and cartilage repair in a rat model of injuryinduced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2005; 13(7): 623-631. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2005.03.003.

46. Nuesch E., Dieppe P., Reichenbach S. et al. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ, 2011; 342: d1165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1165.

47. Petrella R.J., DiSilvestro M.D., Hildebrand C. Effects of hyaluronate sodium on pain and physical functioning in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med., 2002; 162: 292-298.

48. Pinney J.R., Taylor C., Doan R. et al. Imaging longitudinal changes in articular cartilage and bone following doxycycline treatment in a rabbit anterior cruciate ligament transection model of osteoarthritis. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 2012; 30(2): 271-82. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.09.025.

49. Reginster J.Y., Badurski J., Bellamy N. et al. Efficacy and safety of strontium ranelate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results of a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis., 2013; 72(2): 179-86. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202231.

50. Rutjes A.W., Juni P., da Costa B.R. et al. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Ann Intern Med., 2012; 157: 180-191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473.

51. Sampson E.R., Hilton M.J., Tian Y. et al. Teriparatide as a chondroregenerative therapy for injury-induced osteoarthritis. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3(101): 101ra93. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002214.

52. Strassle B.W., Mark L., Leventhal L. et al. Inhibition of osteoclasts prevents cartilage loss and pain in a rat model of degenerative joint disease. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010; 18(10): 1319-1328. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.06.007.

53. Thomas T., Amouroux F., Vincent P. Intra articular hyaluronic acid in the management of knee osteoarthritis: Pharmaco-economic study from the perspective of the national health insurance system. PLoS One, 2017; 12(3): e0173683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173683.

54. Tonge D.P., Pearson M.J., Jones S.W. The hallmarks of osteoarthritis and the potential to develop personalised diseasemodifying pharmacological therapeutics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2014; 22(5): 609-621. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.004.

55. Tortorella M.D., Burn T.C., Pratta M.A. et al. Purification and cloning of aggrecanase-1: a member of the ADAMTS family of proteins. Science, 1999; 284 (5420): 1664-1666.

56. Towheed T., Maxwell L., Anastassiades T., Shea B., Houpt J., Robinson V. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev., 2009 (CD002646). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002946.pub2.

57. Waddell D.D., Bricker D.C. Total knee replacement delayed with Hylan G-F 20 use in patients with grade IV osteoarthritis. J Manag Care Pharm., 2007; 13: 113-121. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.2.113.

58. Wandel S., Juni P., Tendal B. et al. Effects of gluco-samine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis. Br Med J., 2010; 341: c4675.

59. Wang M., Sampson E.R., Jin H. et al. MMP13 is a critical target gene during the progression of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013; 15: R5. doi: 10.1186/ar4133.

60. Zhang W., Moskowitz R.W., Nuki G. et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2007; 15: 981-1000. DOI:10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014

61. Zhang W., Moskowitz R.W., Nuki G. et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2008; 16: 137-162. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013.

62. Zhang W., Nuki G., Moskowitz R.W. et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 2010; 18: 476-499. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013.